In 1909, Theodore Roosevelt Embarked on an Ambitious Expedition to East Africa. Here’s Why His Trip Still Matters Today

The 26th U.S. president is both lauded as a conservationist and condemned as a big-game hunter. A new book recounts the historic journey on which he helped form a significant collection of animals at the National Museum of Natural History

By Brian Handwerk – Science Correspondent

September 23, 2025

On a frigid day in March 1909, President Theodore Roosevelt rode slowly through the streets of Washington, D.C., his horse-drawn carriage navigating nearly a foot of snow and slush on the way to the inauguration of his successor, William Howard Taft. The short trip marked Roosevelt’s exit from the White House, but his thoughts were already on the next great journey of his life.

Before the month was over, Roosevelt again found himself surrounded by cheering throngs at another historic departure. This time, in New York, Roosevelt was boarding the Hamburg to embark on an adventure that captivated people all over the world: the Smithsonian expedition to British East Africa.

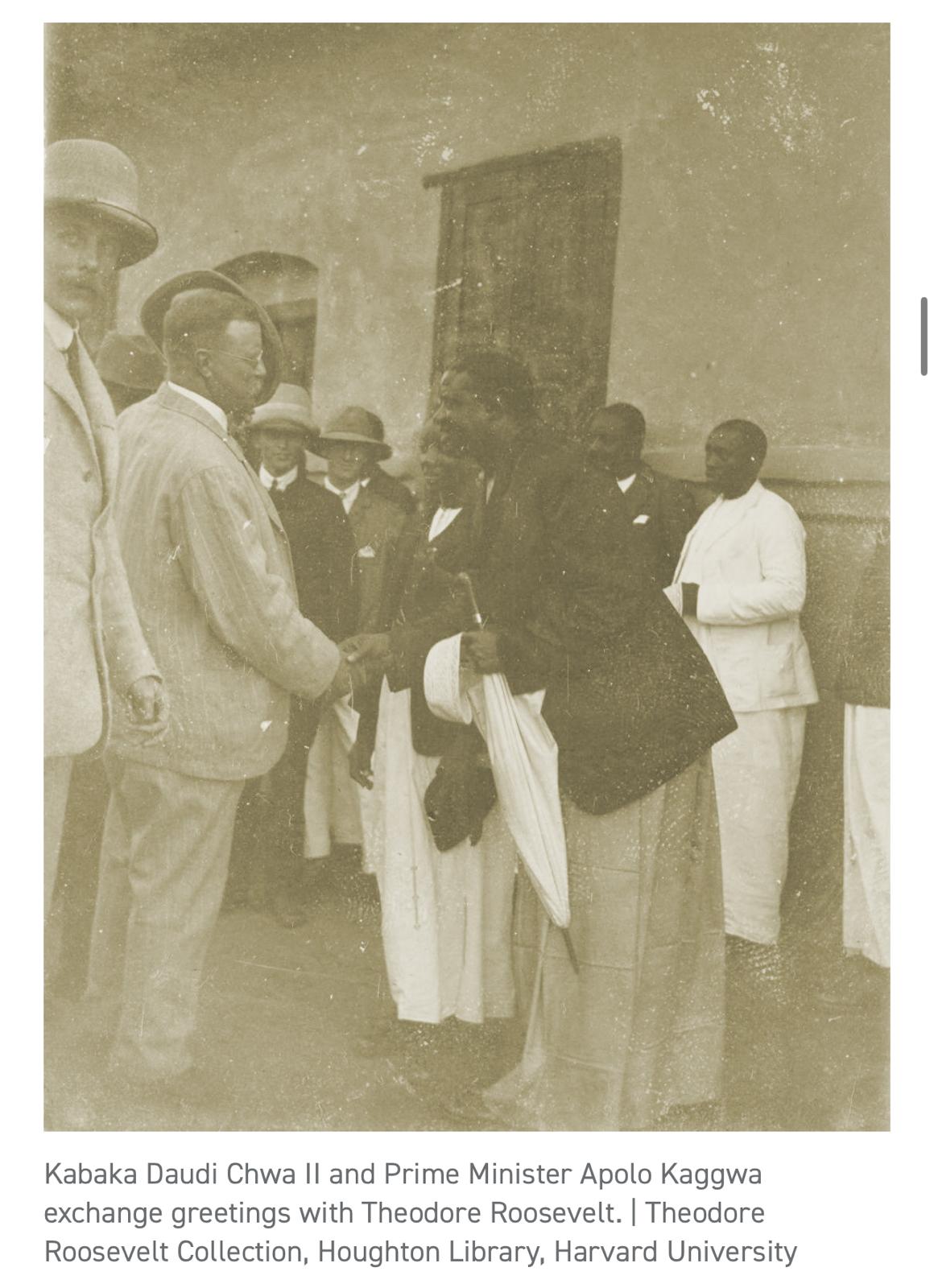

Eager to escape the responsibilities of the presidency and give Taft space to govern, Roosevelt longed to get away, enjoy camp life and take to the field with his gun. Roosevelt and his son Kermit would bag elephants, rhinoceroses and lions—but theirs was no simple big-game safari. The 1909–1910 expedition, through parts of what are now Sudan, South Sudan, Uganda and Kenya, included leading scientists. It produced a written and photographic record of an Africa that few in the West had seen, and it diligently described and preserved hundreds of African animals that became a foundational collection for the newly minted National Museum of Natural History.

In a new title from Smithsonian Books, Theodore Roosevelt and the Smithsonian Expedition to British East Africa, 1909–1910, readers can experience the expedition in Roosevelt’s own words, written during evenings in his camp tent. The book features 28 excerpts from his chronicle African Game Trails: An Account of the African Wanderings of an American Hunter-Naturalist. It’s illustrated with more than 100 fascinating expedition photographs, many taken by Kermit Roosevelt, that capture East Africa’s landscapes, fauna and people. Author Frank H. Goodyear III provides thoughtful historical context and commentary on the expedition’s enduring scientific significance, while exploring how the endeavor reflects the era’s colonial imperialist attitudes toward Africa and its people.

“He saw a long tradition of exploration and seeking out new knowledge, and trying to connect worlds together,” Goodyear says. “Of course, exploration is also part of empire building, so that’s a part of the legacy here as well. But I think he very much saw himself as participating in this history of Western exploration.”

Key Takeaways: Theodore Roosevelt’s Trip to East Africa

- In 1909, just after his presidency ended, Roosevelt and his son Kermit journeyed to East Africa to collect specimens for the Smithsonian.

- These specimens went to the U.S. National Museum, now called the National Museum of Natural History, which opened to the public in 1910.

- The many animal and plant species that Roosevelt and fellow naturalists brought back from the trip are part of an important collection for the museum today.

It was a crucial time for such a trip. Roosevelt saw how railroads and settlers had forever altered the wild landscape of the American West. In Africa, such change was happening quickly. Roosevelt knew it, as did many others who were scrambling to collect and document African species and ecosystems that were on the brink of radical transformation or extinction.

“It’s a real transitional moment in the history of East Africa,” Goodyear says. “Colonization is really beginning to take hold... So it was clear that the impact on indigenous ecosystems was going to be profound.”

Roosevelt’s environmental legacy remains complex. He’s been celebrated as a conservationist and criticized for being a big-game hunter, especially by those who had recently witnessed the destruction of the buffalo and the native ecosystems of the American West.

“It was controversial in its own day, and it remains controversial,” Goodyear says. But Roosevelt was aware of this criticism and determined that this trip would not be an exercise in “game butchery.”

“I would a great deal rather have this a scientific trip, which would give it a purpose and character, than simply a prolonged holiday of mine,” he explained in a letter to Henry Cabot Lodge.

Roosevelt’s passion for the natural sciences was real and lifelong. “Yes, he liked big-game hunting,” says Darrin Lunde, mammals collections manager at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of Natural History. “But he was so much more than a hunter. It genuinely was a scientific expedition led by a former president who himself could hold his own as an ornithologist and a mammalogist.”

He was an eternal naturalist who collected specimens and started his own museum as a child. “He was one of those guys who liked to get out with his gun, collect things, do taxidermy, describe new species,” Lunde says. Roosevelt originally went to Harvard University to be a naturalist, a part of him that always remained.

Planning the trip in the White House, Roosevelt proposed a partnership to Secretary of the Smithsonian Charles Doolittle Walcott: if Walcott would provide naturalists to identify, describe and catalog African species, Roosevelt would donate them as a collection for the new museum.

The Smithsonian pledged $30,000—raised privately—to fund the scientific work. The expedition’s naturalists, Edgar Mearns, Edmund Heller and J. Alden Loring, collected thousands of specimens: mammals, birds, plants and insects. Each was measured, cataloged and preserved for study.

“All of those Roosevelt specimens, for the most part, are still here,” Lunde says. “We have the best collection of East African mammals anywhere, in large part because of the contributions of the Roosevelt expedition.” Scientists continue to study the collection today.

Because Roosevelt was one of the world’s most famous figures, journalists clamored to join the expedition. He rejected them all, preferring to write his own accounts. Scribner’s Magazine paid him $50,000 for 12 field articles, later compiled as African Game Trails. Kermit Roosevelt’s photographs added both scientific and promotional value.

“The photography is what first drew me into this project,” says Goodyear. “They are absolutely extraordinary... more than 1,000 of these photos comprise an incredible record of the people, places and fauna of East Africa.”

Kenyan entomologist Dino Martins contributes an afterword emphasizing the indispensable local expertise that enabled the expedition.

“Though often unacknowledged, that local knowledge and support made it possible for Western explorers to undertake these journeys,” Martins writes.

Despite their essential role, African people are largely absent from Roosevelt’s African Game Trails.

“Outside of himself, Kermit and a few heads of game, nearly all other figures in the book are shadowy,” noted a 1910 Philadelphia Inquirer review.

The Roosevelt expedition also left a lasting scientific legacy. In 2015, a “Roosevelt Resurvey” expedition revisited its routes, rediscovering a rodent species on Mount Kenya described by the Smithsonian team over a century earlier—proof of the collection’s ongoing scientific value.

Though the region has changed dramatically since 1909, conservation work in Uganda’s Ajai Reserve—home of the white rhino once documented by Roosevelt—now draws on those century-old records.

“Without it, efforts to create these parks would just be guesswork,” Lunde says. “Thanks to the Roosevelt-Smithsonian expedition, they are able to refer to a record of what these habitats were like in their natural state.”

Quick links

Trail

Documentary

Agri Hub

News

Contact

social media